The difference between a company that solves problems and one that hides them often comes down to a single reflex. Every company lives in one of two equilibria. One is stable and bad. The other is unstable and good. If you’ve worked at more than one place, you’ve likely seen both.

The Good Equilibrium

In the good equilibrium, when something goes wrong, people get curious. Not polite curious. Practical curious. The kind of curiosity that reflects a sense of ownership.

A team reports a problem and the first response is:

“That’s interesting. We didn’t know that was happening. Let’s investigate. We’ll take point on reproducing it. If it turns out to be an issue on the user side, we’ll help them fix that too.”

It assumes the other team is describing a real experience. It treats the report as a signal, not an accusation. It commits to the next step. And it does all this without prematurely deciding who’s “at fault.”

In companies like this, issues don’t need to “escalate” in the dramatic sense, because they’re already moving.

Someone notices something is laggy or error-prone. They mention it early. The other side investigates. A few hours later there’s an update: what we found, what we changed, what to check now.

When this equilibrium is working, it feels safe. Problems show up, get named and handled. People don’t hoard information because information isn’t ammunition.

This is the equilibrium you want.

Why Good Equilibrium is Unstable

It’s unstable because it requires everyone to keep choosing a harder move.

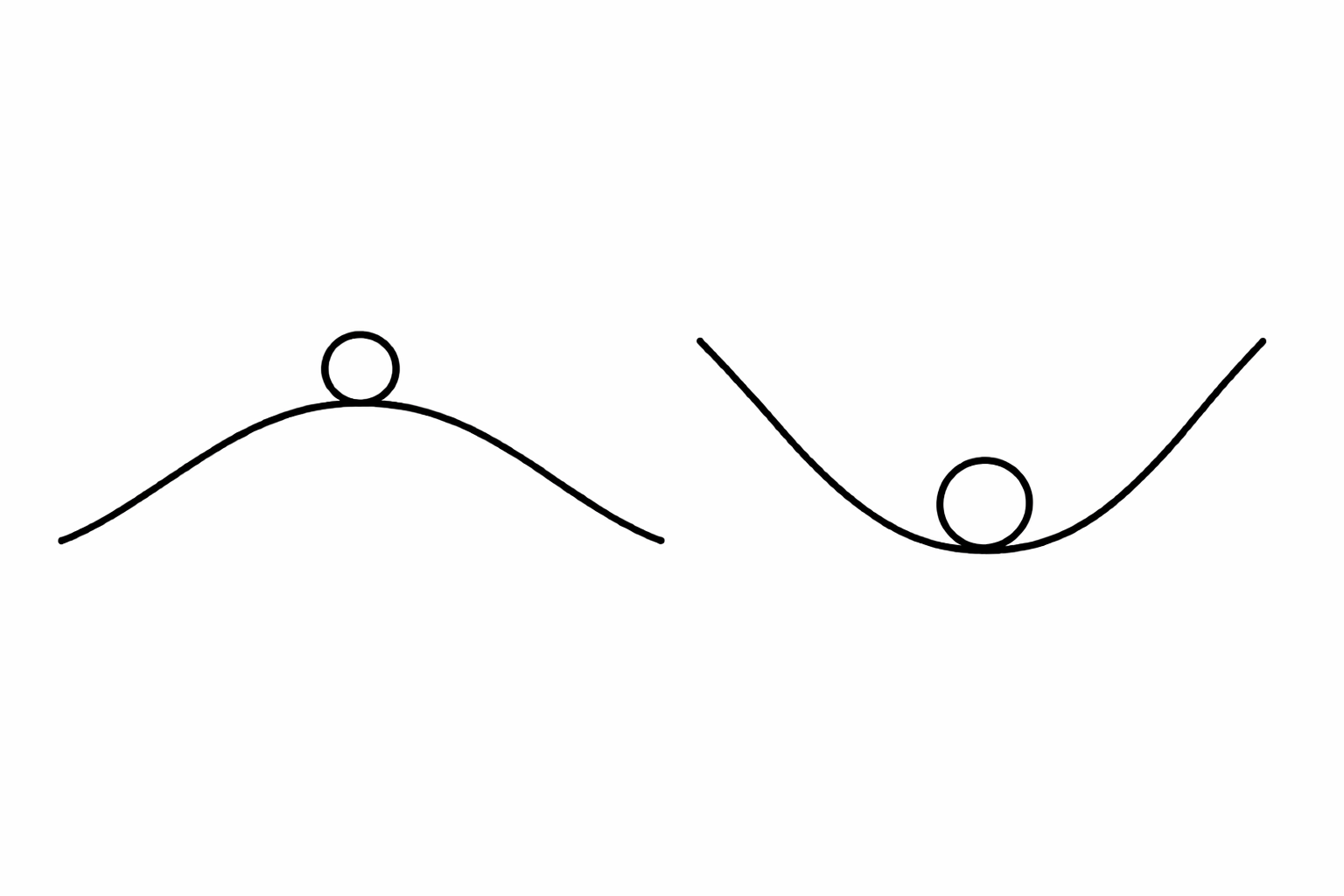

Picture a ball on top of a hill. That’s the good equilibrium. Any nudge, defensive response or blame-shift that goes unchallenged, and it starts rolling. The valley is the stable equilibrium. Once you’re there, climbing back takes sustained, deliberate effort.

The easy move, when a report comes in that might implicate you, is self-protection.

Self-protection looks like skepticism. It often sounds reasonable. It can even be true in the narrowest sense.

But it changes the game.

Here’s something I’ve seen more than once. A finance team (or any operationally heavy team), visibly struggling. Too many people. Too much manual work. Too many mistakes.

Finance says: “The software is laggy. It’s error-prone. It takes forever to do basic things.”

Then you ask the tech team what they think.

If the first response is defensive, you’re not dealing with a software question anymore. You’re dealing with an equilibrium.

The defensive response sounds like:

“We’ve never gotten complaints about that. Everything is running fine. I don’t know what Finance is talking about.”

That response might even be correct on paper. The system might be fine in one environment. It might be fine for most users.

But the point isn’t whether the system is fine. The point is the reflex.

If a team’s first instinct is to invalidate another team’s experience, the company has already learned a habit: When a problem crosses a boundary, your job is to protect the boundary.

All it takes is one person to defect this way a few times, and you get retaliation.

The next time something goes wrong, the other side protects itself.

Once that starts, it begins to feel rational and it builds on itself.

The tech team in this case might be responding this way because they’ve been blamed one too many times.

What Keeps The Good Equilibrium Alive

Some companies resist this longer. Usually it’s because someone at the top actively enforces the good equilibrium with immediate correction. When blame starts, they reset the tone publicly:

“Saying ‘we’ve never heard complaints’ isn’t helpful. The point is, we’re hearing one now. Let’s investigate.”

This changes the payoff structure. If people see defensiveness punished, they stop being defensive. If they see ownership rewarded, they take ownership.

But the same intensity pointed wrong creates the opposite. A leader who reacts to incidents with rage (“what the fuck is going on?”) teaches teams that bad news is dangerous. In that environment, redirecting blame becomes survival.

The key isn’t intensity. It’s what the intensity enforces.

The Stable Equilibrium

In the stable equilibrium, the default response to friction is: “Not us.”

People say it in different ways, but the meaning is always the same.

It shows up first in language. Then in behavior.

First you hear the phrases that redirect responsibility:

- “That’s on ops.”

- “That’s a user problem.”

- “That was a human error on their side.”

Then you see the behaviors:

- refusal to help unless it’s “in scope”

- endless debates about where the boundary is

- ticket ping-pong

- “please follow the process” as a weapon

In this equilibrium, people learn something important: helping is dangerous.

If you volunteer to solve a problem that isn’t “yours,” you might inherit the blame if it goes wrong. If you surface bad news, you might get punished for creating it. If you admit uncertainty, someone might quote you later.

And even if you say nothing wrong, your words might get twisted to fit someone else’s narrative.

So people stop doing those things and they start doing the things that are safe. The safe things are: defend, redirect, document, and escalate.

This equilibrium is stable because it’s individually rational.

Even if everyone hates it, it persists because it protects each person from getting burned.

How Companies Slide Into It

One thing accelerates this drift more than anything else: middle managers managing upward.

A lot of middle managers are trapped. They’re evaluated by people above them. They want to look competent. They want promotions and raises. They don’t want their team to look like the source of problems.

When something goes wrong, they learn to translate it into a version that makes them safe.

Instead of reporting: “We’re blocked. My team hasn’t been able to provide inputs.”

They report: “Tech/Ops/Finance/Marketing/Others couldn’t do it.”

I’ve seen projects nearly derail because the truth was distorted this way.

In one case, we were working with the finance department of an OpCo that had hundreds of people doing work that should have been automated. The goal was straightforward: automate the workflow, reduce manual handling, and scale the output of the team.

The tech work wasn’t the hard part.

The hard part was getting the operational details: what documents are downloaded, from where, in what format, how they’re processed, what exceptions exist, what edge cases matter, so that the processes can be streamlined, either with tech or with process improvements.

We needed inputs from the finance team and they were slow to provide them. They didn’t have a documented process in place. And that’s fine. We’re willing to work together to find the answers and solve the problem.

However, when the finance middle managers were asked by their higher ups, they would almost always imply: “It’s impossible to do. It’s too complicated. Tech says they can’t deliver.”

That one distortion can kill a project.

Because leadership doesn’t see “we’re waiting on finance.” They see “the project can’t be done because it’s too hard.”

Then leadership stops backing the initiative. Various teams stop investing time because leadership stops paying attention. The whole thing becomes proof that “it can’t be done.”

This is the stable equilibrium doing what it does. It turns truth into a liability.

Conclusion

The stable equilibrium is stable because it protects everyone individually while failing everyone collectively.

The good equilibrium requires people to keep choosing responsibility over self-protection. And they won’t keep choosing that unless the environment rewards it.

Somewhere right now, a tech team is saying “we’ve never gotten complaints about that,” a finance team has learned to stop asking and a middle manager is managing upward.

The drift has already started. It started the first time someone deflected and no one corrected them.

The question isn’t whether your company will feel this pull. Every company does. The question is whether you’ll notice it happening and resist the gravity.